Alternative Liquidity Capital Announces Offer to Purchase Shares in FS Energy & Power Fund

Alternative Liquidity Capital is providing an opportunity for investors in FS Energy & Power Fund to sell their shares. Here is a copy of the recent press release summarizing the offer.

Alternative Liquidity Capital has announced an offer to purchase up to 1,000,000 shares in FS Energy & Power Fund (the “Company”).

The Company’s share repurchase program has been suspended since March 2020 and may continue to be for an indefinite period of time Consequently, liquidity is extremely limited for shareholders. The Offer provides an opportunity for legacy investors to exit their investment in the Company. Unless extended, the Offer will Expire on September 20, 2022.

The Purchaser is a Delaware Limited Partnership and is not affiliated with the Company. The Offer is being made solely for the Purchaser to establish a passive ownership position in the Company.

Shareholders should read the Offer and related material carefully because they contain important information. Shareholders are urged to consult with financial and other professional advisors before making any decisions regarding the Offer. This announcement is intended as a notification that the Offer has been made, and does not constitute an invitation to sell. Any action that any Shareholder may take in relation to the Offer is only able to be taken once they receive a copy of the Offer which contains the applicable terms and conditions.

Shareholders may obtain a free copy of the Offer and Assignment Form without charge by visiting Alternative Liquidity Capital’s website at: https://www.alternativeliquidity.net or by calling (888) 884-8796. Investors may also contact the Purchaser at info@alternativeliquidty.net to answer questions about the Offer or to obtain Offer documents.

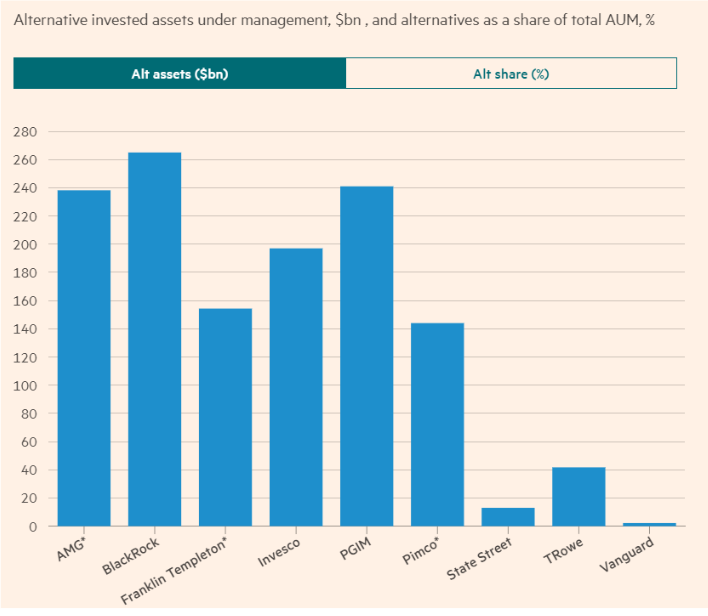

Alternative Liquidity Capital will also purchase other non-traded alternative investments. If you illiquid assets you are looking to sell please contact info@alternativeliquidity.net